GENUS & SPECIES

I think there are a few facets to the question posed in the title. But before we get to that, I think we need to define what a villain is.

A villain is a type of antagonist. Every story has an antagonist, someone or something that opposes the hero or heroine, even if it’s the setting as in Jack London’s “To Build A Fire” or the hero himself as in Jim Carrey’s Liar Liar. But usually the antagonist is another character in the story.

Antagonists vary in many ways. One way that’s important to the story is how sympathetic they are. The spectrum runs all the way from those who generate fear and loathing to those who generate just a little less sympathy than the hero. Note: we can never feel more sympathy for the antagonist; the moment we do, they become the hero in our eyes. The definition of the antagonist is the person we’re rooting against, the person who is working against the person we’re rooting for.

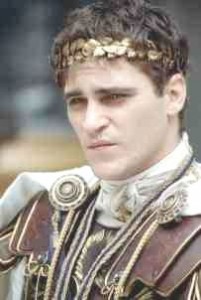

So a villain is a species of antagonist that generates fear and loathing in the reader. It doesn’t matter if they think they have good reasons for their acts. We still feel they are evil and dangerous. Examples include: Darth Vader, Sauron, the kidnapper in Mel Gibson’s Ransom, Commodus in Gladiator, or the Joker in The Dark Knight.

So here’s what I’ve noticed about effective villains.

VILLAINS & STRUCTURE

1) In a villain/hero story situation, the villain is key because the hero is reacting to the villain’s plan. It’s a total threat/danger plot.

2) So the villain has to be active. He’s the one who WANTS something. He’s the one that starts the whole story. A weak villain isn’t going after this thing whole-hog or doesn’t have the power to do it or has no urgency and will.

3) Strong villains are ruthless AND powerful. Villains also need to have some brains–we need to be worried for the hero, remember? We have to know that they’re they type of person that will take you out if you get in their way. Even if they have a well-spun way of making themselves sound ethical. But villains go beyond other antagonists in that we fear and hate them. They are evil.

4) The hero needs to be the underdog in the relationship, meaning less powerful, two steps behind, not as easily ruthless etc. The bigger the plan the more high stakes and high concept the story becomes. But it’s the villain’s plan that drives it. And they will be taking steps to counter the hero, will probably be two steps ahead most of the story.

5) As always, as with any character, the villain’s plan and motives have to be believable. Even if they are evil. The minute a villain becomes too far-fetched, they lose their power.

CHARACTER INTEREST

In addition to the role villains play in the story, there are a number of other things that make them interesting. However, these things are not anything new or different. They’re the same things that make any character (or person) interesting.

– Larger-Than-Life Attributes (as in experience, power, skill, success, position, or behavior)

– Eccentricities and Particularities

– Outrageousness

– Humor

– Beauty

– Surprise (as in against type details, reactions, motivations, or backstory)

– Inner Conflicts (as in the “ethical” dilemmas they find themselves in)

While danger and threat draws the attention, rouses interest, and can be sufficient to make a villain memorable, I think the factors mentioned above have a wonderful effect.

THE CORE QUESTION

The root question when considering villains is what pushes readers toward the fear and hate of others?

Of course, it’s relative. But there are qualities that engender these feelings in us. Selfishness, brutality, sadism, madness, cruelty, a complete disregard for others AND the power to carry their wishes out. It’s someone who poses huge, immediate, specific threats to me or those I care about and does it without any concern or with relish. The more intense these factors, I think the more we move along the spectrum towards fear and hate.

So people say the best villains are those who are the hero’s of their own story and with whom we can empathize. I don’t think this is accurate. The Joker in the Dark Knight was a great villain and may have been the hero of his own story, but never in a million years would I empathize with him. It’s true we can smpathize more with people who agonize and resist horrible acts. And some antagonists do show scruples. But not every story demands that type of antagonist. Sometimes what’s needed is someone who kills grandma horribly and says “so what” or “it was fun”–and engenders fear and hate.

One last point. “Villain” is a reader attributed characteristic, i.e. the reader is the one who labels the character. This means the person has to be a villain in the READER’S eyes, not necessarily a villain in the eyes of the culture in the story. For example, In Not Without My Daughter the hero subverted and violated the dominant story culture, and I cheered for her. The guy who was sustaining the moral order of the story culture was the villain.

ROOTING

From what I can tell, all rooting response is based on some innate sense of justice, of what’s appropriate in a situation. For whatever reason, we feel discomfort when undesireable things happen to good or innocent people. We also feel discomfort when desireable things happen to bad people. The reason why we root for someone is because they have a lack of happiness or a threat to their happiness AND we belive they deserve better. I can’t see anything else we based that deservingness upon except some inner sense of justice.

It doesn’t mean the deserving person is a goodie two-shoes. It just means that in the context of the story and what’s happening, we think the scales of justice tip, if only slightly, to the hero’s side.

Some may argue this, but I don’t think it’s possible to root for someone or against someone without a moral judgment. It’s true that not every antagonist needs to or does act immorally. In fact, the antagonist might be doing the right thing, the moral thing, in his or her particular situation, and it just happens to oppose the hero’s desires. The key however, is that the story guides the reader to feel the hero should win at the antagonist’s expense. And that it’s right for the hero to do so. That “rightness” is based on a moral stance of what’s good and desireable in the given situation. The farther along the spectrum of antagonists we move towards villany, the more clear that moral stance becomes.